You’re stoked! It’s a beautiful autumn weekend, and you’re going to a new climbing area. You’ve been training hard all week, and you’re in crushing mode. You show up, and the climbing area looks amazing. Overhangs, crimps, and big dynos galore.

The temperature is brisk, perfect for sending, but you look around and there’s nothing to really warm up on. The routes are either too easy or too hard.

You say, “f**k it,” and go up a route anyways. The rock is cold. You’re fingers are cold. They’re actually getting numb, so much so that you can’t really feel the holds. So, you start over gripping to compensate for the lack of feeling, and then it comes...the dreaded pump.

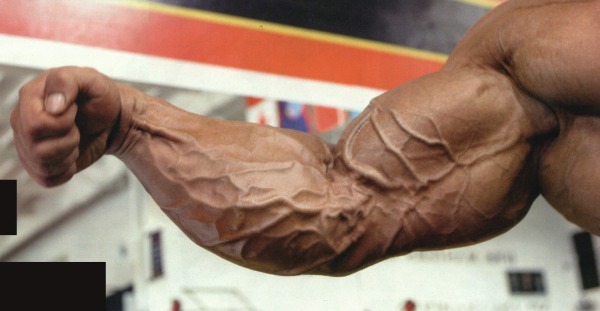

Climbers get pumped forearms due to multiple intense contractions of the muscles that restrict blood flow. The contractions continues because the restricted blood flow does not let metabolic waste and energy (i.e ATP) flow through the muscles to allow them to relax.

The pump is a nasty fellow that likes to stick around. You try to shake him out, but he’s persistent. He also likes to mess with your head making you doubt that you got enough strength to make the next move. Just when you think you got the pump out, but you’re pumped right away on the next route, and it’s a struggle. You’re not performing, you’re surviving. And your stoke is slipping away.

Next time keep the stoke up and warm up!

Most of us know that a proper warm up is important before doing strenuous activities because it improves performance and prevents injury. However from  the arm circles and toe touches I’ve seen at the climbing gym and at the crag, many climbers don’t know what a proper warm up should entail.

the arm circles and toe touches I’ve seen at the climbing gym and at the crag, many climbers don’t know what a proper warm up should entail.

As its name implies, a key component of a proper warm up is heat. Exercises should be done to heat up the muscles. Studies have shown that increased muscle temperature leads to increased performance1. By increasing muscle temperature, contraction and relaxation response, nerve transmission, and metabolism are all elevated.

An equally important component of a proper warm up is increasing blood flow. Warming up opens blood vessels that are dormant when a body is at rest. Blood vessels are like conveyor belts for the muscles delivering nutrients and oxygen, and taking away waste like lactic acid. Increasing the amount of blood to the muscles allows them to perform more efficiently.

Besides the physiological benefits, warm ups help to mentally prepare athletes for peak performance. A common practice among successful Olympic athletes is the frequent and deliberate use of mental performance exercise1. Activity-specific warm ups allow for better visualization, and high intensity warm ups prime the body to tolerate discomfort from maximal effort.

One side note, stretching is not an effective warm up, especially static stretching. While not completely conclusive, many studies have shown that statically stretching large muscles, where a muscle is stretched to its limit and then held for 20 to 30 seconds, can reduce a muscle’s explosive strength 2,3. Some researchers believe the decrease in strength is a result of relaxation of the tendons due to prolonged elongation2. Others believe static stretching impairs neurological function that causes muscles to generate force4.

So how does one warm up?

Your warm up should include these concepts:

- Think more workout rather than stretch.

- Make it a full body workout.

- Elevate your body temperature.

- Include anaerobic and aerobic exercises.

- Dynamically, go through the full range of motion for joints and muscles.

- Progressively increase the difficulty of the exercises.

- Do sport-specific motions.

Dr. Jared Vagy's Book, "Climb Injury-Free."

I personally like doing a 7 minute full-body workout that progressively gets harder, kind of like a HIIT (High Intensity Interval Training) workout. It ticks most of the boxes. I’m very warm with a slight sweat on my body, I’m breathing heavy, and I’ve mentally endured a difficult exercise. After, I’ll do climbing specific movements like alternate drop-knee lunges, finger tendon glides, hangs (two arm hangs, and one arm hangs). I discovered many of these movements from the book, “Climb Injury Free,” by Dr. Jared Vagy, (a.k.a. The Climbing Doctor). Next, I work out my antagonist muscles to maintain muscular balance and avoid injury. Once again, I use many of Dr. Vagy’s recommended exercises for the antagonist exercises. Then I do a warm up route that I can climb smoothly and technically, and finally, I climb!

And it feels good to climb at this point. Compared to not warming up, there are less aches, more mobility, and less hesitation to pull real hard or commit to a dynamic move. My finger joints and hip flexors especially appreciate the warm up.

Eddy's 7min Full Body Warm up Workout:

- 30sec Jumping jacks

- 30sec Air squats with finger flicks

- 30sec Mountain climbers

- 30sec Hollow body hold

- 30sec Push ups

- 30sec Supermans

- 1min Burpees

- 30sec Crunches

- 30sec Leg raises

- 30sec Alternating side planks

- 30sec Tricep dips

- 30sec Handstands

- 30sec Hangs

PAP experiments by Dr. Tyler Nelson.

Recently, I have included a post activation potentiation (PAP) routine at the end of my warm up derived from Dr. Tyler Nelson’s recommendations, a chiropractor who specializes in climbing. PAP is a theory that athletes can prime muscles for higher exertion of force by subjecting target muscles to high loads for short durations so as not to cause fatigue5. Dr. Nelson’s investigations on PAP have shown promising use for climbers, especially for boulderers who use more fast twitch or Type II muscle fibers. I use PAP for grip strength by doing 7 second isometric pulls on the 20mm edge of my Flash Board at maximal intent; then rest 20 seconds; and repeat 2 more times. All that is done at one elbow angle. I perform the exercise at three different elbow angles with a minute rest between angles. The angles are slightly bent elbows, 90 degrees, and 120 degrees or like the final position of a pull up. After these pulls, I feel amped to climb hard.

This may seem like a lot of time and exercise, but know that it’s common for elite athletes to warm up for 30 minutes or more. My warm up routine takes about 15 to 20 minutes. It seems like a lot of time, but I enjoy the warm up because I know what it feels like not to warm up properly (I sometimes do), and it sucks. I also justify my warm up by viewing it as a workout that maintains the more mundane tasks of athleticism like mobility training, weight maintenance and strength training.

An important note to consider for an activity like rock climbing is the stop and start nature of the activity. There are long periods of time when you are not climbing like when waiting for a route to open up, belaying your partner, or just lounging and chatting on the comfy bouldering mats. Be sure to keep your muscles warm and the blood pumping before you start climbing again. I like doing a shortened version of my PAP routine as the isometric exercises allow me to load my fingers slowly toward maximal intent.

Now most people might think my warm up is fine and dandy for the climbing gym, but impractical for the crag. And they would be right in that I don’t do the exact workout at the crag, but I incorporate the concepts into my warm up. For example, I’ll use the approach to the crag to get my full body workout (nothing gets me sweating like a brisk hike with a backpack full of gear). Climbing specific movements like drop knees lunges and finger flicks can be done anywhere, and I bring my handy dandy super portable Flash Board for my PAP, but you could use holds on the rock as well. Once you commit yourself to warming up and realize its advantages for climbing performance and overall health, you’ll find a way to do it anywhere.

- Courtney J. McGowan, et al., “Warm-Up Strategies for Sport and Exercise: Mechanisms and Applications,” Sports Medicine, November 2015, Volume 45, Issue 11, pp 1523–1546.

- Monoem Haddad, et. al., “Static Stretching Can Impair Explosive Performance For At Least 24 Hours,” Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research, DOI: 10.1519/JSC.0b013e3182964836)

- McMillian DJ, Moore JH, Hatler BS, Taylor DC. Dynamic vs. static-stretching warm up: the effect on power and agility performance. J Strength Cond Res. Aug 2006;20(3):492–499

- Jeffrey Gergley, et. al., “Acute Effect of Passive Static Stretching on Lower-Body Strength in Moderately Trained Men,” J Strength Cond Res 27(4), 2013

- Daneil Lorenz, “Post Activation Potentiation: An Introduction,” International Journal of Sports Physical Therapy, 2011 Sep; 6(3): 234–240.